The Sandpaper Principle of Scale

There is a way of working that is essential to any creative pursuit, design especially, that is woven so deeply into the process itself that we don’t really have a good way of talking about it. And yet every good designer, and successful team that I’m aware of does it, and ignoring it can be catastrophic, no matter the size of the project.

I’ve come to think of this concept as the Sandpaper Principle, which is an analogy that happens to make sense to me, though I’ve also heard it partially articulated through concepts like “working lean” and the “Minimum viable product (MVP)” The idea goes like this:

Say you want to build a chair out of a tree using hand-tools.

First you would start with the coarsest, most efficient, least precise tool in your arsenal; an ax.

Next, you would move to a slightly more precise tool to convert the lumber into rough boards; a saw.

Next you square the boards up with a jointer and plane, slightly more precise, yet still rough tools, and so on until the chair is largely made, at which point you start with the coarsest sandpaper, say 100 grit, down to the finest, say 600 (or bust out the 000 steel wool and make that bad-Larry sparkle).

This is the most efficient way to work. From coarse to fine, ax to sandpaper. This is the first rule. The level of resolution required at a given stage of development dictates the tool that you use.

Equally, you don’t want to skip ahead to a finer tool than is necessary for the given application. Attacking a tree with 600 grit sandpaper is just as Sisyphean as trying to smooth a delicate surface with an ax. It seems obvious (even a first-year student toiling away over a pile of blue foam understands this concept intuitively), but I can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen people ignore this in the process of design, even at very high levels. And this concept applies to every creative process that I’m aware of, from writing to sculpting, to CAD modeling, even presentation and storytelling.

Where Things Go Wrong

This tends to manifest in a few ways. In some cases, the actual purpose of given milestone in a project isn’t always clear at the start, and so there’s a mismatch in requirements. Say you’re asked to develop a quick concept for a widget so that everyone can have a reference point for a client meeting. A few storyboards or a low-res model would have communicated the idea to the team, but instead you went down a rabbit hole, hopped into CAD and went H.A.M. on some dope renderings with tasteful CMF and realistic depth of field… only to find out that the idea wasn’t worth exploring (and worst of all, now the client is confused, thinking you’ve done all this work on a bad idea. More on that later).

This can really be exacerbated when people design in a vacuum, without good team input and structured deadlines. A lot of designers have a perfectionist streak (definitely calling myself out here) and a tendency to fall in love with their own ideas, but this can get wildly out of control when there is a lack of creative confidence on a team (i.e. a toxic environment that is not conducive to failure, resulting in creative stagnation). If your team is always poking holes in your concepts and building up their own ideas, the first impulse is to overthink and overdevelop your concepts out of insecurity, wasting time making them unassailable instead of collaborating towards a solution. This kind of isolation can be deadly to a creative department and should be avoided at all cost.

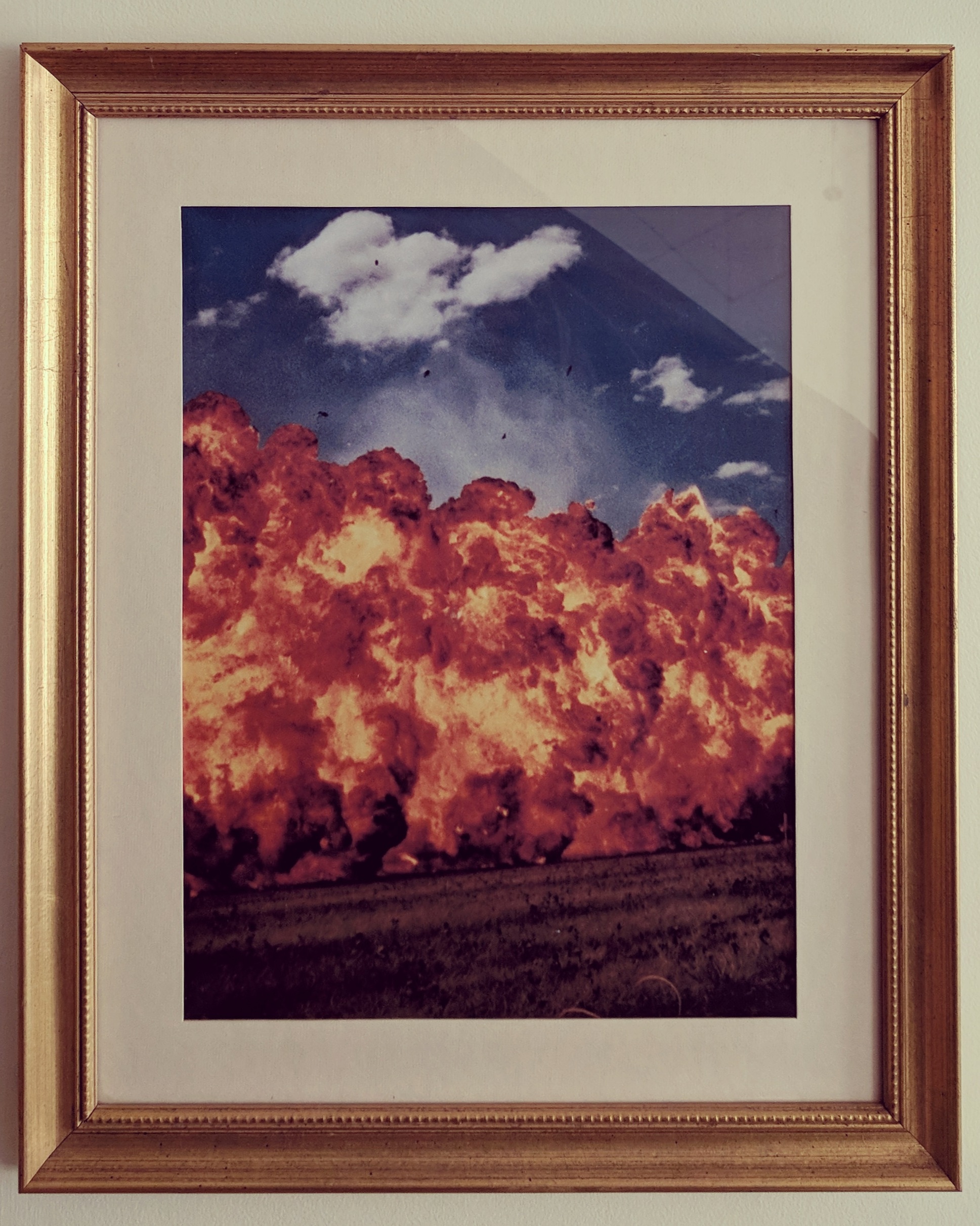

This problem definitely isn’t limited to creative departments. I’ve seen this work its way up to the scale of major company projects; hundreds of thousands of dollars, and months of dev time just to overshoot the target, or come up short because the deliverable wasn’t scaled appropriately for success. In one instance from my own life, a company decided that a massively complicated, pre-production prototype was necessary to meet business goals, but only had a small team and an insanely aggressive timeline. Rather than balancing what was actually needed with what was possible, the team took their marching orders and blazed ahead, burning themselves out and blowing through piles of cash before it was too late. The end result was half-assed, underwhelming and cost the company dearly.

Tuck Your Chain: A digression on keeping it ugly

This can actually lead to a related failure, the “What You See Is What There Is” phenomenon; when you see something that looks like it belongs in a further stage of development than it does, it will be interpreted and judged in that context. In other words, if you make it look like a finished product when it’s just a proof of concept, people will critique it as though you’ve spent months honing in every last detail. Sometimes it’s a good idea to make something look intentionally rough so that people (clients, studio partners, whomever) can set their expectations, and understand how they should view and judge a concept.

In other words, tuck your chain. Don’t let your gems show, lest they be snatched.

And this doesn’t just apply to prototypes; as Michael DiTullo said in this interview, “a rendering is a statement, a sketch is a conversation.” Getting too precious with your hand skills during a brainstorm is a good way to get stuck on idea 1 while everyone else is on idea 20.

Avoiding Splinters

Here are some practical ways of avoiding using the wrong grit at the wrong time:

Understand what success looks like first: When someone drops a new project in your lap, always try and understand the context before you put pen to paper. Ask three things: what, why and when — stay the hell away from how until you have those answers. Getting caught up in how you might do something before you know the requirements of the deliverable itself (the why and what), and how much time you have to complete (when), it is a sure way to over or under shoot the project. And sometimes the person asking you won’t have a full picture of the challenges or risks involved in what they’re asking for, which brings me to my next point…

Scale deliverables through negotiation: A very wise friend of mine once said: “Don’t just come up with problems. Offer solutions.” Success in design is always about balancing what’s possible within limited constraints and what’s desirable, usually from the client or management. If the initial project scope isn’t feasible, treat the first ask like a first sketch and build off it! Make sure they understand the challenges, but offer some appropriately-scaled alternatives; if a full prototype isn’t necessary to get good customer feedback on one feature, how about a concierge demo? Be creative and hone in on the minimum viable product.

Get out of your own head: Seek feedback often during your process, and if you don’t have a safe space to do it, consider finding ways to get feedback from people outside of your immediate team. We all know this as designers, but it can be hard to realize what’s happening in the moment. Follow your intuition. I tend to get a creeping feeling when I’m getting a little too precious about something, and that’s a great time to pull someone in for a sanity check.

Starting Over

The Death of DesignxHustle

I started writing the blog DesignXHustle in my final semester at Mass Art. At the time, it was a way for me to record my process as I tried to take an idea to market, the CocoNest, which I had won an honorable mention for in that year’s IHA Student Design competition. Both the product and the blog were part of my senior capstone project at Mass Art, which was centered around Millenials and entrepreneurship. Now, four years into my career, I’ve realized that I want a platform to archive my process, elucidate ideas, and create a record of my growth and experience… but looking back over the old posts, the discontinuity is just a little too jarring.

For one thing, I got some things wrong

My senior capstone consisted of two full-semester classes centered on a simple prompt; design a product for Millenials. The first semester was spent conducting user research; creating a methodology, interviewing fellow Millenials, and synthesizing the findings into a brief. We started quite broad, trying to understand the unique challenges faced by our (my) generation, and in the end, narrowed in the focus of my research on work.

It seemed to me at the time, that my generation was obsessed with side hustles and starting their own companies in a search for meaningful work, and as an escape from the pitfalls of traditional labor. It seemed to me that what most Millenials craved was a work-life balance, and not only a job but a career that they cared about, and the most expedient route to that was to start a business.

And so, for the second half of my senior year, I decided that I would go through this experience myself, taking a product from idea to market (or at least as close as I could get it) and then create a resource that Designtrepreneurs like myself could use to more effectively bootstrap their own revolutionary products. Hell, I’d already started a relatively successful Etsy shop called Durable Goods Manufacturing Company, and already had a sense of what it would take to work with manufacturers, build a website, market my product, etc. I’d learn a bunch, and maybe kick start my career with a successful (hopefully) crowd-funding campaign.

In the end, I didn’t take my product to market, and I didn’t really solve any problems for my fellow Millenials, searching for meaning through self-employment. I graduated, handed in my final assignment, and got a job in the industry.

Post Mortem

I have some thoughts on why this happened. It has become clear since this time, that the Millennial fixation on side hustling has more to do with their alienation from traditional labor and lack of fulfilling opportunities, and the startup craze is the result of a lot of capital floating around in the market looking for a good idea that it can attach itself to, if only to be used to claim a tax loss for the extremely rich. Neither of these things have resulted in a better work-life balance for my generation, and in fact it’s ludicrous in retrospect that I thought this might be the case.

If anything it seems to have lead to more exploitation, and more general anxiety, and indeed, most people that I know, especially the successful ones, live extremely stressful lives with very little balance. You will know them by their oft-repeated mantra — “sorry for the delay, this week has been crazy but things should calm down soon”.

That’s not adulthood, it’s capitalism.

That said, I do still believe in the power of bootstrapping, and crowd funding, and entrepreneurship, and the democratizing the means of production, and “innovation” and all of those romantic things that got me into this field in the first place (more on that in a future post). Some very interesting products and creative projects have come about thanks to these things, especially ones that serve populations largely ignored by the mainstream, and I do think it’s true that working for oneself can be a more robust position than working for a traditional employer, with boundaries.

However, in trying to bootstrap my own product, I ultimately came to the conclusion that it wasn’t worth following through on. It had potential, I think, and lots of other people did as well, but I wasn’t happy with the solution at the end of the day, and I wasn’t about to go into dept tooling up to produce a thing I didn’t feel good about, certainly not once I found myself with my first real job designing medical devices.

But in the end, the experiment was a success, even in its failure. I learned a lot, I made a thing, I graduated, and ultimately I got a job that would lead me to even more opportunities to learn, and make, etc.

The real treasure was the friends we made along the way

What Comes Next

For now, I’d like to have a space to expand on some ideas that have been percolating in my brain over the last few years. What design can do for the world and its limitations; how things have changed and continue to change; where people fit into all of this; and where I fit in as well. It’s a prototype, and I hope that it is a useful tool for understanding more about myself and the things that I am passionate about.

In a more practical sense, I do intend to archive the original DesigxHustle blog as a separate page connected to this one, and I have what I think are some interesting and hopefully rewarding regular columns like The Oblique Philosophy Corner and Billion Dollar Ideas, in addition to writing on whatever weird ideas come to mind. Expect some weird PoMo design theory and plenty of extremely subtle Marxist ideology, fam.

I hope you’ll join me.